Being John McEnroe (happy Birthday, bastard)

In the heavily chronicled career of tennis star John McEnroe, there is a match that received little attention but drew such ire from his opponent, Johan Kriek, that Kriek decided he couldn't take it anymore. After the match, he was nearly apoplectic and demanded McEnroe's ouster from the tour.

In the heavily chronicled career of tennis star John McEnroe, there is a match that received little attention but drew such ire from his opponent, Johan Kriek, that Kriek decided he couldn't take it anymore. After the match, he was nearly apoplectic and demanded McEnroe's ouster from the tour. "I'm sick and tired of (McEnroe's) bullshit," Kriek said. "If I'm the only one that has the guts to say he needs to be kicked off the tour, fine. I work too hard to be treated like this. That guy McEnroe has got a screw loose."

Given that McEnroe's comportment once led The New York Times to call him "the worst advertisement for our system of values since Al Capone," Kriek's comments, as well as McEnroe's actions on the day in question, may not shock: First he demanded the chair umpire have the lights on a nearby practice court turned off and when questioned by her about his request, snapped back, "Don't give me that crap." Later, when a serve was called out, he screamed to the lineswoman, "Get the hell off the court, lady," then smacked a ball that just missed hitting her.

This was two years ago on the Seniors Tour.

Needless to say, McEnroe, now 42, husband and proud father of five children, Emmy-nominated tennis broadcaster and the short-lived captain of the U.S. Davis Cup team, has lost little of the intensity that made him one of the most compelling athletes of our time. Whatever it might say about the current state of men's tennis, eight full years after leaving the pro circuit, and after an aborted attempt to become a rock singer -- which he took far more seriously than he'll ever admit -- McEnroe remains the most captivating, controversial and explosive figure in the game.

My time will come or whatever

On a crisp spring morning near Richmond, Va., where McEnroe has come to play another seniors event, he is sipping a cappuccino outside Starbucks and allowing a rare glimpse into his hyper-analyzed career and psyche. With his match against former Argentinean star Jose Luis-Clerc still hours away, he is dressed dowdily in faded blue jeans, black leather boots, and a black vinyl jacket zipped to the neck, a look that is at once brusque and disarming. A silver hoop earring clings to his left ear and a black Yankees cap is pulled so tightly over his creased forehead that sprouts of gray hair protrude clown-like from the sides. His menacing metallic blue eyes are hidden behind dark wraparound sunglasses.

Yet despite his cloaked visage and our unlikely suburban locale, McEnroe is hopelessly recognizable. As we are talking, an elderly blind man who had tapped past us with a walking stick moments ago, returns to our table and says in McEnroe's general direction, "Excuse me sir, you must be John McEnroe."

In the past this sort of interruption would have prompted an explosive and cruel retort, but now after a tense and protracted silence, McEnroe finally says, "That's right," and shakes the man's outstretched hand before dismissing him curtly with a mocking "G'day mate."

If nothing else, McEnroe has come to accept, and even take some delight in, the fact that his raspy New York-inflected pipes have become the official voice of tennis, a game that before his arrival on the scene was played like a silent film in green and white.

He's well aware of the irony, but his brash, unapologetic manner suggests the remarkable ubiquitousness he has maintained in the game is beyond his control. Remarking on the retirement and canonization of a fellow New York sports star, hockey's Wayne Gretzky, McEnroe says in the matter-of-fact tone that has won him a huge following as a broadcaster, "I guess there's a little part of me that's like, 'Wouldn't it have been nice if I'd received that adulation?' Well, I'm not as nice a guy as Wayne Gretzky."

But to believe that McEnroe is beyond caring about what people think of him is to fall prey to the manipulations of a man who feigned illness and left the charity event he was throwing in London three years ago when told his band was going to follow instead of precede the night's special guests, Led Zeppelin. And a man who has learned to use the broadcast booth as a bully pulpit, eventually strongarming the game's organizers and executives, many of whom would be happier never to hear from him again, into appointing him to the highest and most visible post in U.S. tennis, Davis Cup captain, a position he petulantly held for a year before resigning in frustration in November after the U.S. was thumped by Spain in the semifinals.

Along the way, McEnroe has come dangerously close to becoming the thing he always claimed to hate most -- a phony -- portraying himself during telecasts and in interviews as a man-of-the-people who rides the subways and tells it like it is, while in his spare time he's shilling for companies like Nike, Heineken, Lincoln Navigator and Rogaine, and collecting cars and homes as if they were tennis trophies. His carefully chosen marketing deals, negotiated by his hard-driving consigliere father, John Sr., a corporate lawyer for a major Manhattan firm, have netted him an estimated $100 million, far more than anyone else to have played his sport. Not bad for the only player in history not to be granted an honorary membership to the All England Club when he won Wimbledon for the first time, in 1981, a slight he wore then as a badge of honor.

Yet despite his popularity and riches, and perhaps even because of them, McEnroe seems deeply disappointed with his life. On a recent afternoon that he spent in his SoHo gallery collecting memorabilia to bring with him the International Tennis Hall of Fame, where he was enshrined in 1999, he betrayed a sense of desperation and remorse about his place in the game.

"Now it's, 'Oh, John is sooo good at commentary,'" he said, fidgeting with his birds-nest hair while sitting on a maroon love seat. "It's like, Hey I was pretty good at tennis too, but I didn't hear that the same way. My time will come or whatever. If it comes at all."

A fine line between genius and insanity

In a career that spanned 16 years beginning in 1977, McEnroe won 77 career singles titles (3rd behind Jimmy Connors and Ivan Lendl), ranked No. 1 for four straight years from 1981 to 1984, and commanded our attention like no other player before him or since. But for someone who many in the game consider the most talented player of all-time, he ranks a surprising tenth (tied with nine others) in Grand Slam titles, with seven, behind Pete Sampras (13), Roy Emerson (12), Bjorn Borg (11), Rod Laver (11), Bill Tilden (10), Ivan Lendl (8), Jimmy Connors (8), Fred Perry (8), and Ken Rosewall (8). Worse, he didn't win any after turning 25 in 1984, when he seemed to have just hit his stride -- but had already become his own worst enemy and was blowing his top, both on and off the court.

As he does so well when analyzing tennis on television, McEnroe can be equally insightful, and often stunningly candid, when speaking about himself. In a detached, wizened tone, he explains that the on-court tirades during his pro career became "like a cigarette addiction. It's not really what I'm feeling, I'm just doing it because it's the habit. I'd go out on the court and suddenly I'm doing something and I'd be like, 'Why am I doing this?'"

But after years of searching for the answer, including several rounds of therapy, he still hasn't been able to escape the demons. Yet while he will openly discuss his past, when his take-no-prisoners attitude gave him a certain anti-establishment appeal, he takes special care to conceal that his emotional struggles continue to plague him in a very real way. Some senior tour organizers have considered banning him from their events entirely, but McEnroe has sidestepped criticism by proclaiming in every conference call and interview he does, this one included, that his boorish behavior is a "big joke" carried out for a crowd intent upon seeing the signature McEnroe meltdown.

In reality, the mostly middle-aged, country club crowds at the seniors events are hardly capable of experiencing schadenfreude upon seeing a middle-aged man have a hissy fit. Often they come away offended, or in the case of a 10-year-old boy who was hit by a water bottle thrown into the crowd by an enraged McEnroe at a Chicago event last July, slightly injured and tearful.

Mac's fellow players, for the most part, just shake their heads. "I see it but I don't understand it," says former Wimbledon champ Pat Cash, a friend of McEnroe's and an occasional participant in the seniors events. "It's a fine line between genius and insanity in anybody who's the best at anything. John is the best player that's ever walked on a tennis court in my opinion. He also always walked that line. Sometimes he goes over it."

Wimbledon, 1977

Why McEnroe insists on remaining so involved in a game that creates such havoc in his life is a question not easily answered. But it is revealing that McEnroe feels like he never chose his pursuit. Tennis found him, he tells me in Richmond during the first of our meetings, and it has certainly kept its hold on him as he has on it since the very first moment he shot onto the scene as a pale, unathletic-looking 18-year-old. In fact, this particular moment --Wimbledon, 1977 -- is the only thing that McEnroe feels bears mention when asked to talk about turning points in his career, as if it separates some distant previous life from the one he's been living ever since.

He had just graduated from a private high school in Manhattan, where he was a top student and a gifted athlete who loved any team sport, and particularly basketball and soccer. But even though he never trained or practiced regularly, his quick feet and soft hands made him a natural at the solitary game of tennis. He was the runner-up at the 18-under national junior championships in his senior year of high school and earned the chance to play the Wimbledon qualifying tournament from which a few players would win wild cards and advance to the main draw. Two weeks later, he found himself in the semifinals on Centre Court opposite Connors.

"Before that I never thought about what I wanted to do," he says, the foam from the extra dry cappuccino he's slurping forming a white mustache on his upper lip. "Tennis was such a lonely game. I never liked being out there alone. But after that I had to at least try."

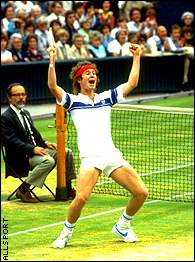

Something else unexpected, and equally significant, also happened that fortnight. In his quarterfinal match against Phil Dent, Mac had got angry with himself when he lost the first set and he began bending his wooden Dunlop racket under his foot. For the first time in his life, he was booed. "I thought it was hilarious," he says. "I wanted to see what would happen so I kicked my racket across the court and they booed again. I loved it." But he was shocked when he picked up the papers the next day. The London tabloids had christened a monster: "SUPERBRAT."

"I had no idea that would translate to America and become such a big deal," he says. "I grew up in New York. You go from the airport to your house and you're lucky if ten people don't call you an asshole. Look at hockey players -- put a mike on them, or put a mike on the football field. I'm just like those guys, but they made it look like it was all different."

Of course, it was. Tennis had seen vile (Connors mock masturbating with his racket between his legs); it had seen abusive (Ilie Nastase berating linespeople); but no one had ever quite witnessed McEnroe's combination of exquisite athleticism and almost maniacal explosiveness. One moment, he would stab at a volley he had no business getting to, angling it perfectly into the opposite corner, the next he would be frothing, screaming, and smashing television equipment. The crowds, particularly at the beginning, despised him; the sport's organizers were in a tizzy. All of which had the effect of making McEnroe, a wise-guy kid who was known to jump over the subway turnstiles yelling "U.N. Delegate," more determined to expose and depose the "phonies" who ran the sport.

"The game was so stiff," he says now, launching into his favorite rant. "It felt like everybody's collar was starched, like the next thing they were going to do was ask me to wear long pants. So if there was one thing I wanted to change that was it. It became like this cause for me."

But in the end, tennis remained relatively unchanged and McEnroe nearly sunk himself in the pursuit.

Nothing less than perfection

For years, there were murmurs that McEnroe damaged his career through drug use, particularly because in the mid to late '80s, when he was prematurely dropping in the rankings, he had fallen in with a decidedly Hollywood crowd, married (and later divorced) actress Tatum O'Neal, who has since been in and out of drug rehabs, and, of course, generally acted like a raving dope-addled lunatic. In the past, McEnroe always vehemently denied those rumors, but as we're driving back to the Comfort Suites outside Richmond so he can get ready for his match against Luis-Clerc, he admits for the first time that they weren't completely unfounded.

"I wasn't an innocent bystander," he says, pulling closed the car door he'd started to open when we come to a stop in front of the lobby. Cocaine was the drug of the times, he says, but though he experimented with it, he says he didn't let it affect his game. "I could see early on that it wasn't something I could do if I wanted to keep playing," he says. "It's a whole process, you're up late, then you want to sleep all day. It wasn't conducive to being a professional athlete."

And though there were times in 1986 and '87 when he took several months away from the game, his friends who agreed to talk about the subject say they did not think cocaine played a role in his declining career.

Certainly McEnroe's intensity was not reliant upon drugs. Martin Chambers, the drummer for the Pretenders and a longtime friend, remembers visiting him at his beach house in Malibu in 1986. They were shooting pool and McEnroe suggested they put some money down. With $50 on the table, they racked up another game in which Chambers went on a run to win. McEnroe was furious. "He threw his stick down on the floor and he meant it," says Chambers, laughing at the memory. "He was angry. But that's what made him so great. You've got to want it really bad."

McEnroe not only wanted it perhaps more than anyone except maybe his hated rival Connors -- who is generally recognized as the most competitive man to have played the game in the modern era -- but also he truly seemed to expect from himself nothing less than perfection. He was and still is the only player in the game who gets ticked almost every single time he misses a shot. It is a trait he inherited not from his father but his mother Kay, who, when John Sr. came home years ago and announced he'd finished second in his class at Fordham Law, told him, "If you studied harder you would have been first."

After McEnroe's crushing 6-1, 6-1, 6-2 defeat of Connors to win Wimbledon in 1984, a match many believe was the most flawless display of tennis ever -- McEnroe made a total of two unforced errors -- he said: "I think I can, hope I can, play even better."

This inability to accept anything from himself but the impossible beau ideal helps clear up one of the most misunderstood aspects of McEnroe's legacy. For all his talk about, and lasting reputation for, challenging authority, many of his outbursts (though often not the ones that made the 5 o'clock news) were actually directed at himself, a self-loathing that no amount of success or distance seems able to quell. Even in the 1981 first-round Wimbledon match against Tom Gullikson, in which two of Mac's most famous umpire-bashing phrases were born ("You cannot be serious!" and "You guys are the pits of the world"), his fulminations had begun with frustration over his own play. Despite the fact that he was ahead the entire match and won in straight sets, when he hit a volley long in the second set, he screamed out, "I'm so disgusting you shouldn't watch. Everybody leave." If Connors had said it, the crowd would have roared with laughter; instead you could have heard a strawberry drop. Coming from McEnroe's scowling, contorted mug, it was painful to watch.

Mesmerizing tennis

At the same time, his tortured persona in combination with his shotmaking genius turned his matches into gripping, balletic psychodramas. When he would stop dead in his tracks with his hands on his hips and his top lip clenched in his bottom teeth, we had no idea what was rumbling through his veins or how violently it would erupt. Yet somehow, barely composed, he was often able to punctuate his rage with an anger-inspired rocket-ace as if to say Take That, or even more incredibly, with the most delicate, impossibly-placed drop shot that seemed to have come fluttering off the strings of a Stradivarius. He may have become the bete noir of the tennis establishment, but people who never gave a crap about the sport before were suddenly mesmerized. Andy Warhol followed him around with a camera. Tom Hulce studied him for his role as the eccentric, half-crazed 18th century composer Mozart in the 1984 film Amadeus.

Why should McEnroe have cared that the All England Club denied his membership when Mick Jagger is holding up a Rolling Stones show to meet him, David Gilmour of Pink Floyd is inviting him to studio sessions, and Jack Nicholson is greeting him with that cat-like grin and the emphatic words, "John-ny Mac. Don't ever change." The circa early 1980s black and white Nike poster of McEnroe walking an empty New York side street in a trench coat over the inscription "Rebel With A Cause" perfectly captures the rarefied (and oddly sexless) James Dean/Holden Caulfield appeal that the young McEnroe cultivated: the outsider who's too good to ignore and too cool to change for anyone else, protocol be damned.

For those who dealt with him on a regular basis, it meant constantly walking on eggshells. "He's made more locker rooms uncomfortable places," says one former pro who now works with the tour. "That hasn't changed. One day he may come in and say 'Hi,' and ask about your family, the next he could just go off on you for no reason. Most of us just try to steer clear."

As much as McEnroe may claim he's grown out of the puerile behavior, he seems to get some pleasure, if not a psychic release, from acting out from time to time. There was the show-stopping, backstabbing nationally televised speech three years ago at the dedication of the Arthur Ashe Stadium in which he deviated from the text he'd been sworn to in order to bash the USTA; the incident in his apartment building in 1995 in which he roughed up an elderly neighbor who'd claimed he was monopolizing the elevator, screaming "I know who you are, you're a lousy schoolteacher;" his firing a tennis ball at the head of opponent, and friend, Mel Purcell at a seniors tournament in New York two years ago that caused Purcell to refuse to speak to McEnroe for six months; and his erratic performance in front of record company executives at CBGB in 1997 that may have cost his band a record deal. "If he would have been reprimanded more seriously early on, he may have been better off," says Bud Collins, who McEnroe insisted be removed from NBC's broadcast booth when he signed on with the network in 1994. "The rules never applied to him."

Emotional outbursts and tactical arguments

McEnroe's opponents are nearly unanimous in their opinion that his on-court behavior was not the raw impetuosity of a mad genius as we were led to believe, but rather the contrived tactics of a champion so arrogant he would do literally anything not to lose. Brad Gilbert, who played McEnroe 15 times on the tour, winning only once, remembers a match he played against McEnroe in 1986 in Los Angeles in which he was tied with McEnroe in the final set 3-3.

"I hit a backhand passing shot down the line to go up 0-30 and the ball was clearly in," Gilbert says. "He turned that into a 15-minute argument. People were getting impatient so he started screaming at somebody in the stands, just working somebody so bad that a fight broke out, and -- this I've never seen before -- the umpire ends up having to call security to the stands. Finally after a 15-minute break after somehow pulling all this off, I didn't win like one more point."

Purcell, also a former tour player, recalls a third-round match he played against McEnroe on clay at the French Open in 1984. Purcell, who never ranked higher than 21, had broken out to an early 4-2 lead in the first set when McEnroe suddenly started complaining about the condition of the court. "It was a little chopped up," Purcell says, "but I was playing on it, too. But he started going on about how he won't continue playing unless the maintenance people come out and redo the court. Nobody else could have gotten them to do that. So we go back into the locker room for a half hour, and he's in there ranting about how stupid the French were. By the time we got back out on the court I'd lost the momentum, and he beat me easily."

McEnroe used similar tactics against the top players in the game, including Connors, Jim Courier, Sampras, Lendl and Boris Becker. "He was the most difficult player to play against," the recently retired Becker told me, "because it was always personal with him. It was never just about tennis." Says Pat Cash, "The rule book was like 100 pages long. By the time McEnroe retired it was like 250. It's phenomenal how many rules they had to bring in for him."

The only player McEnroe never acted up against was Borg. They had several memorable matches, but none more so than the 1980 Wimbledon final, which many consider to be the greatest tennis match ever played. Mac was 21, with long curly hair springing out in all directions from a red headband, a nasty, unreadable serve, and an unorthodox, tumblefoot-and-hop move to the net that would inspire a generation of serve-and-volleyers, including Cash, Becker, and Stefan Edberg. Borg, the stoic 24-year-old Swede, was lean and chiseled, with loping strides and smooth, classical strokes.

The match lasted nearly four hours; one hour and six minutes of it coming in the titanic fourth set, a tie-breaker won by McEnroe, 18-16, to even the match at two sets apiece. In the tiebreaker, McEnroe fought off seven match points, one time running from end to end and somehow firing a crosscourt backhand winner from so far off the court he was almost in the stands.

He had deadly precision on his volleys and a topspin lob that was disguised better than Mata Hari. In the end though, Borg's consistent, beautifully angled groundstrokes finally won out in the fifth, 8-6 (no tiebreak is played in the fifth set at Wimbledon). Of the 482 points played in the match, Borg won 242 to McEnroe's 240. Not once did McEnroe lose his head.

Even more than his great wins, McEnroe loves to remember that match and, oddly, isn't bothered at all by the fact that he lost. "I'm just glad to have been a part of something that special," he says. "It's certainly one of the highlights of my career." It was as if only when playing Borg -- whom McEnroe considers, along with 1960s great Rod Laver, to be the best ever -- did he remember how beautiful a game tennis could be. He forgot the trappings of being the mad artist and focused on the canvas.

"He had very few peers," the late Arthur Ashe once said of McEnroe. "So he gets bored and condescending with others and has to manufacture controversy to stay interested."

No surprise then that his greatest year -- 1984 -- was also one of his most bombastic. First in the French Open final, he blew a two-sets-to-none lead against Lendl after losing his temper, and then his game, tearing the headphones off a CBS soundman's face because he claimed the noise from it was disrupting him. He never reached another final at Roland Garros and the absence of a French Open title from his resume remains a conspicuous omission.

A couple weeks later in England at the pre-Wimbledon Queen's Club tournament, he won handily but made it a field day for the tabloids when during the final he called the chair umpire an "idiot" and yelled out, "Over 1,000 officials to choose from and I get a moron like you." When Mac saw his opponent, the relatively unknown Leif Shiras looking amused during his outburst, he pointed his finger at him during the changeover and warned, "I've been around a long time and I don't want to take that crap from you."

Silence Him Now! screamed the Daily Mail. Even the staid Guardian opined, "No one should be permitted to voice such contempt for a fellow human being and get away with it." Despite the furor, McEnroe managed to get through Wimbledon relatively unscathed and dusted Connors in that nearly flawless final. After winning the U.S. Open in what would turn out to be his last Grand Slam victory, he wrapped up his incredible 79-3 season at a tournament in Stockholm by memorably smashing a courtside tray of drinks with his racket during a match after not getting a response from the chair umpire when he screamed out, "Answer the question, jerk!" That incident put him over the $7,500-fine limit that had been instituted almost singularly because of him, and he was suspended from the tour for 21 days.

The hiatus

"I didn't care too much at the time," McEnroe admits now. He had just met his first love, actress Tatum O'Neal, at a party in Los Angeles, near where he had bought Johnny Carson's Malibu beach house. They appeared a perfect match. Her erratic behavior had earned her the nickname Tantrum; he said she "reminds me of a female version of myself." The first major event to which O'Neal traveled with him was the Australian Open in December, 1985. They checked into Melbourne's tony Regency Hotel and quickly made a pact: They weren't going to let the media rattle them. Then McEnroe went downstairs, grabbed an overeager reporter by the neck and tossed him over a chair. He merely spit on the photographers.

On the court he was hardly any better; he was fined so many times during the fortnight that he once again went over the limit and was suspended from the tour after losing in the quarterfinals. This time he stayed away, of his own volition, for seven months. It was then that the drug rumors began to surface. O'Neal was pregnant and McEnroe's head wasn't in the game. He had started losing to players he would have beaten in his sleep in the past. "I was feeling a little spent," he says now. He was often seen without Tatum at Hollywood parties and backstage at Van Halen, Billy Squier and Eagles concerts, but he says the beginning of his decline wasn't due to drugs but the overwhelming pressures and responsibilities of family life.

From the year his first child was born in '86, until '91, he won only 11 of his 77 titles and was running his career-fine tab up to almost $90,000, still a record. After becoming the first player in the modern era to be booted out of a Grand Slam tournament at the Australian Open in 1990 (for appealing the umpire's decision to dock him a point for racket abuse by telling the supervisor of officiating, "Go f--- your mother") and then losing in the first round at Wimbledon several months later, he had an emotional reckoning. In the bungalow where he was staying in London, Patrick McEnroe says his older brother admitted to him and longtime doubles partner Peter Fleming that he felt like he'd let the people who cared about him down. "It was a tough time," Patrick says. "John said he wasn't going to let himself go out a loser."

Aware that physically he would soon be unable to continue to play at the same level, McEnroe made a final push in 1992 at age 32, reaching the quarterfinals of the Australian Open, the semifinals of Wimbledon and the fourth round of the U.S. Open, his best showing at Grand Slams since '85. But in the process, he may have cost himself his marriage. In December, the week before the Davis Cup finals against Switzerland, in which McEnroe would make his final appearance playing for his country, O'Neal told him she wanted out, reportedly because he had insisted she remain at home with the kids rather than return to acting as she'd wanted. News of the breakup made the cover of the National Enquirer, the New York Post and the New York Daily News. In one of her few public comments about McEnroe, O'Neal said, "I've had a lot of experience with men who are bullies, but taking on John McEnroe was the biggest struggle of my life."

A great team player

"I don't think she honestly believed that for a second," McEnroe says now when asked about O'Neal's comment. "I think her father (actor Ryan O'Neal) was a far bigger bully than I ever could have been. I certainly never hit her. I think that was said in anger." Nevertheless McEnroe was devastated, and spent most of the week of the Davis Cup, which was being played in Dallas, hiding in his hotel room to avoid the sea of tabloid reporters there to cover the breakup.

Fortunately, because McEnroe had long since been surpassed as the top one or two American singles players, he was there only to play doubles, a circumstance that might have both kept him from spinning completely out of control and guaranteed a U.S. victory.

One of the most overlooked aspects of McEnroe's career is that he not only may be the greatest doubles player of all-time, but also that he was, and still is, a different person when he wasn't out on the court alone. "The only time he seemed to really enjoy himself was playing doubles," says his close friend and occasional doubles partner, former pro Tom Cain.

McEnroe's success and incredible ability to fire up his partner and his entire team in Davis Cup competition, make him quite possibly the greatest team player never to have played a team sport. His frequent doubles partner Peter Fleming, when asked once who he thought was the best doubles team of all-time, responded, "McEnroe and anyone." He won eight Grand Slam doubles championships, equaled his singles tally with a record 77 doubles tournament titles, and his impact on the U.S. Davis Cup team was almost Jordanesque.

Mac the iconoclast loved competing for the red, white and blue, and he led the United States to five world titles while compiling an unsurpassed 59-10 match record in the 12 years he played Davis Cup. One of his most memorable lines to an umpire came during a Davis Cup match against Argentina earlier in 1992, when after what he perceived as a bad call, he said to the American chairperson, "You're not just hurting me, you're hurting your entire country."

At the start of that final Davis Cup match in Dallas, however, he and his partner Pete Sampras, whom McEnroe as Davis Cup captain may have alienated by questioning an injury Sampras used as an excuse for not playing, looked overmatched. They dropped the first two sets against Switzerland's Marc Rosset and Jakob Hlasek and with the packed house gone silent, seemed on the verge of putting the United States in a 2-1 hole. But as McEnroe began trash-talking to their opponents and screaming encouragement to Sampras, they were able to stay alive by winning the third set, 7-5. Then when the U.S. squad went to the locker room for the 10-minute break before the next set, all hell broke loose.

"Mac started just going crazy," says Jim Courier, who along with Andre Agassi rounded out the team that year. "I've never quite seen anything like it. He was just jamming all over Pete and all over all of us, yelling 'We're going to go out and kick some ass.' It was all fire and emotion."

When McEnroe and Sampras got back out on the court, they bulldozed the Swiss, winning the final two sets 6-1, 6-2. Whenever they won a point, Agassi and Courier shouted from the bench, "Answer the Question!" -- sampling, so to speak, from one of Mac's famous philippics. Even the normally inexpressive Sampras became animated, yelling and pumping his fists. When it was over, Sampras told Mac he loved him and then said of his newfound emotions, "I don't think people have seen that from me before. I think I learned how to use it." When Courier won his singles match the next day to guarantee the U.S. victory, McEnroe, who had been screaming from courtside throughout Courier's win, grabbed a huge American flag and ran around the court with it in his upraised arms.

An art dealer and an analyst

"That week was sort of magical," McEnroe says now from his spacious second-floor SoHo gallery, which became a part-time home for him during the messy separation that followed the Davis Cup victory. "I sort of felt like, if I never play again, that would be the way to go out." The walls of the cavernous loft space, now home to the John McEnroe Gallery, are covered with oversized modern art paintings, most notably some by McEnroe's favorite, the expressionist painter Jean-Michel Basquiat, who translated his emotions into colorful, contorted graffiti-strewn profiles before dying of a heroin overdose at age 27. On the coffee table are drawings done by his three kids with Tatum (he has two more with new wife Patty Smyth, formerly the lead singer of the band Scandal). And in the corner of the room, leaning against a standing rack of framed movie posters is one from the 1973 picture Paper Moon, which depicts the film's stars, Ryan O'Neal and nine-year-old Tatum.

Their relationship remains complicated at best, mostly because they have a joint custody agreement with the kids. The arrangement has been difficult for McEnroe. Several years ago, while he was overseas doing commentary for the French Open and Wimbledon, he was so upset by his and Tatum's inability to communicate that he says he briefly went back into therapy. Asked how they get along now, he says, "When is this story coming out? Hopefully, we'll still be talking then."

The gallery, which is now open by appointment only, hasn't been a huge success. McEnroe had developed a respectable collection of American contemporary art in his playing days and opened for business in 1993. His enthusiasm waned, however, when he realized that in order to be taken seriously he would have to cultivate new artists. The endeavor never had his full attention. "When you've been competing for so long, it's not so easy to switch to 'Hey, you wanna buy a painting?'" he says.

Even commentating, which many know him for best now, began and remains most important a very public forum to air his often controversial opinions and lobby for things like getting the Davis Cup captaincy without even having to talk to the people who make the decision. Just like with his playing, he was such a natural as an announcer from the beginning that his producers at NBC, CBS and USA let him get away with things others would have been fired for. In one of his first press conferences as an analyst, just before CBS's coverage of the 1993 U.S. Open, he ignited a firestorm by saying that despite the network's choice of his childhood friend, the well-respected Mary Carillo, as its lead announcer, "women shouldn't be (broadcasting) men's tennis" because they couldn't possibly understand the men's game, just as men shouldn't call women's matches because "how would they know how women are feeling at a certain times of the month."

"He doesn't come to meetings and he doesn't do interviews, but there's certain things you overlook when someone is that good," says Bob Mansbach, executive producer of CBS Sports. "The same things that made him a great tennis player are what make him a great announcer. Plan A, B, C and D immediately occur to the guy, at which point he can analyze and talk about them as well as recall a story or previous conversation he had. I think a lot of what you do is just try to stay out of his way."

Even McEnroe's detractors in the game will admit they learn from his insights as an analyst. And he's loosened up the telecasts with his unique, shoot-from-the-hip style. On USA, which covers the early rounds of the U.S. and French Opens, he even convinced the producers to let him do a live call-in show during the night broadcasts, and he once broadcast part of a U.S. Open match while standing on his head after telling viewers he would do so if Richard Krajicek blew all six of his match points in a fourth set tie-break with Jan Siemerink.

Rock n' Roll hero

McEnroe's greatest ambition, however, from the time he left the tour in '92 until only a few years ago, was to become a rock star, something he has rarely spoken about for fear of ridicule. He had started playing guitar years ago, learning from the likes of friends Eddie Van Halen, David Gilmour, Eric Clapton, Billy Squier and Foreigner's Mick Jones. And with his divorce and custody battle going on in the background, he formed a band with himself as lead singer and guitarist, and began writing songs. His favorite, called "Best Of Me," had a grunge sound with an ominous chorus that went: "Want you to get the best of me/ Accept me as I am/ Breaking out of my own insecurity/ Deal with it, baby/ No more arguing about arguing/ Not this trip again/ No more yo-yo man."

He also met Patty Smyth, the singer of "The Warrior" fame. They fell for each other quickly and he named his band The Johnny Smyth Band, though she rarely sang with them and, some friends believe, wasn't thrilled about his musical pursuit. After one gig in Paris during which Patty had made a rare guest appearance, they had a huge blowout in front of the band. Patty felt that John had tried to upstage her by going into the crowd for a solo during her song. He argued that he was trying to make more room for her on the stage.

As he gained more confidence from playing small gigs in New York and in various international cities where he was playing seniors events, McEnroe signed on with a music promoter to do a worldwide tour and to record an album. To do so, he dropped his original band members and picked up some industry pros, including John Conte, who had been the bassist for Earth, Wind and Fire; George Recile, who played drums for Keith Richards's band; and Patty's old friend Keith Mack, formerly the lead guitarist for Scandal. As his producer, Mac snagged the well-respected veteran Eddie Kramer, who had worked with Led Zeppelin and the Rolling Stones.

"John was really focused on it," says Lars Ulrich, the Metallica drummer who often stopped by to jam with McEnroe in the two-story music studio McEnroe had built on the roof of his huge four-story Central Park West apartment building. "He has a really good natural instinct for music."

But McEnroe hated having to deal with a dubious press and presumptions of dilettantism. Clubgoers weren't so friendly either. At some shows, he was pelted with tennis balls. The owner of Rebar, a Manhattan bar where McEnroe's band played several gigs, says, "We loved having him, but he couldn't sing to save his life." McEnroe stuck with it, however, taking voice lessons and eventually recording 10 original tracks, including "Best of Me," and "Politics," a hard-rocking song in which he criticized the government as useless and confessed to never having voted.

The Johnny Smyth Band toured 15 countries over the course of two years, mostly playing in small clubs. On stage, his intensity that turned to rage on the court translated into charisma. Dressed in a purple, custom-embroidered, western-style shirt, black jeans, and Doc Martens, he shook, swooned, and swung like a tried and true rock star.

"He has the personality to be a great frontman," says Pretenders drummer Martin Chambers, who filled in for a northwest U.S. leg of the band's club tour in the summer of 1996. "When he goes for a solo, he really goes for it. I'll never forget the great enthusiastic look on his face when he looks back at me after he's just hit a perfect note. It's fucking brilliant. Like he can't believe it himself. He's pulled it off and the people are cheering. It's priceless."

But as the album got closer to being finished and the band's gigs were getting better, McEnroe suddenly quit without warning or explanation in the fall of 1997, four months after marrying Patty at a small ceremony in Maui. (When a paparazzo tried to take their photo after the wedding, it was Patty who clocked him with her purse.) It was as if he realized that he was standing at the point of no return. To continue would have meant a full-time commitment with no guarantees and at 38, and with a new wife, he wasn't willing to take the risk. "I think it was a combination of fear of success and fear of failure," says Peter Gold, who managed McEnroe's band.

Life after tennis?

Gold's observation may prove to be a fitting epitaph for McEnroe. He appears earnest about wanting to find equanimity. He says he's doing yoga and trying to cut back on his schedule to spend more time with his wife and kids. (It's not always easy: His 13-year-old son, Kevin, recently banned him from his basketball games for being too vocal a spectator.)

But he is constantly dreaming up new schemes. "I'm thinking about trying to do a sports talk radio show," McEnroe said. He also pitched USA an idea for a soap opera spoofing the art world, in which he would star, but he says simply, "They didn't go for it." And he even muses idly about politics, calling the current state of U.S. politics "despicable."

"I don't necessarily believe that's where I'm headed," he says. "But I certainly get interested when I see what someone like Jesse Ventura is doing."

Needless to say, there is a reckless quality to his pursuits that seems to stem not from an over-inflated ego but from his own exasperation over the fact that after all these years he's still not able to choose his own path. It always leads back to tennis.

After giving up on his rock dream, he quickly rededicated himself to the game, working out almost daily with brother Patrick (who succeeded him as Davis Cup captain). He knocked Connors off the top of the surprisingly competitive seniors tour and began making threatening pronouncements about a return to the main circuit. Meanwhile, he re-upped with the seniors tour for 12-14 appearances each year for the next two years.

After he resigned the Davis Cup captaincy in frustration over the lack of support from U.S. players and International Tennis Federation officials who make the schedule, he has lobbied in his own inimitable way to get the USTA to let him open a national junior tennis academy on the grounds of the U.S. Open in Flushing Meadows, N.Y. "I'd like to think I could inspire kids if I had a tennis academy," McEnroe says, "but it's like I'm talking to a brick wall. What should be a like a slam dunk is considered like McEnroe mouthing off again. They (the USTA) claimed they were going to consider it. Have I heard from anyone? No."

Pacing the floor of his gallery, he takes a deep breath and says, "You have to keep reminding yourself to stop and smell the flowers." But he doesn't stop for long, and the intensity of each new pursuit is beginning to make his career arc feel like a prelude to the scene in the horror movie where the character returns to the monster's lair to retrieve some seemingly unimportant personal item, only to die a gruesome death.

McEnroe actually seems to accept this notion, perhaps even to the point of understanding that the monster is inside him. But he also clearly believes that if he can keep at it long enough, he'll eventually get out with what he wants -- even if it's simply respect, the one thing he's never been able to give himself. Whether he attempts to insert himself back on the pro court again to play doubles, as he continues to suggest, or sticks to coaching, playing seniors, or calling it from the broadcast booth, McEnroe's made sure he's as much in the game as he ever was. "I've never retired," he says, proudly. "That's one thing I've never done. To this day, I've never announced my retirement."

By Julian Rubinstein

1 comentario

Kevin Rosero -

Hi -- the New York Times reported the day after the match that Borg won 190 points, McEnroe 186. I did my own count and I have Borg at 192, McEnroe at 184.

What is the source for the numbers you used above?